The Africa Twin is one of the most beloved Hondas to never have been imported to the United States. In 1986, the NXR750 Africa Twin factory racer made its debut at the then Paris-Dakar Rally. The bike was powered by a V-Twin engine, while the rally largely took place on the African continent – hence its Africa Twin namesake.

Following racing success in the epically grueling rally, Honda produced the XRV650 Africa Twin in 1988 and 1989 which used the same 647cc V-Twin engine as the Hawk GT, then followed by the XRV750 Africa Twin from 1990 to 2003 for foreign markets. Thirteen years after discontinuing that model, Honda has revived the Africa Twin moniker for 2016 as the CRF1000L, and this one is destined for the USA.

The Paris-Dakar rally is now known as just the Dakar and has relocated to South America due to safety concerns in Africa. So too has the new Africa Twin moved on, a parallel-Twin engine configuration replacing the V-Twin of the old XRV750. Of course, everything about the CRF1000L is new, especially the ones outfitted with Honda’s second-generation Dual Clutch Transmission (DCT).

DCT-equipped models were of the Tricolour persuasion, a color scheme (not coming stateside) nod to the original 1988 XRV650 Africa Twin. In South Africa, left is the correct side of the road.

Sticking to the Africa Twin’s historical roots, Honda chose South Africa as the launching site for the company’s new flagship ADV bike; a two-day riding smorgasbord of asphalt, dirt, water, mud, rocks and rain. Occasional wildebeest, baboon, and eland sightings ensured we weren’t mistaking the semi-arid deserts of South Africa for the very similar ones of Southern California.

Day-one riding was largely confined to asphalt and stock tires, and divided between the pre-lunch hours aboard the manual transmission model, while post-lunch was all DCT. Knowing that DCT would later command complete attention, the AM time slot was spent focusing on the Africa Twin’s essential performance characteristics and technologies.

The 998cc parallel-Twin, while significantly more powerful than the V-Twin it’s replacing, is certainly no firebreather. Honda’s claim for the new Africa Twin’s Twin is 93.9 crank horsepower at 7500 rpm, and 72.3 lb-ft of torque at 6000 rpm – enough to spin the rear tire on asphalt or dirt but not poised to steal any performance thunder from the likes of KTM’s 1190 Adventure. The new engine’s low 10.0:1 compression ratio should help it equal the bulletproof reputation and low-maintenance for which its predecessor was renowned – and allow it to run on low-grade fuel – while also keeping the amount of engine braking low. Increasing the engine’s performance envelope will be a simple matter of farming the aftermarket for performance upgrades such as a pipe, cam and pistons.

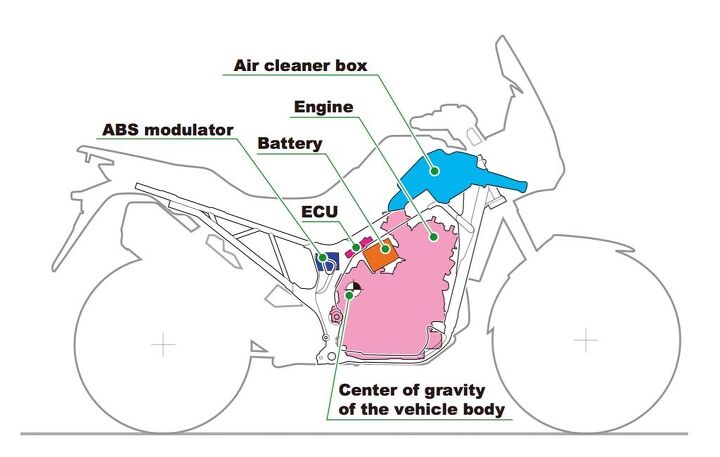

The parallel-Twin configuration was chosen because it allows for tight packaging, and increased mass-centralization. The handling benefits are a bike that feels lighter than its 503-pound claimed wet weight.

Power production from the Twin is a steadily increasing flow of horsepower and torque with no noticeable dips or peaks. Like the CRF450R, the CRF1000L uses a unicam head to more efficiently operate its four valves per cylinder, as compared to a DOHC design. Standing on the side of the road watching other journalists conduct photo passes provided audible proof of the great job Honda did making the 270-degree-firing parallel-Twin and stock exhaust sound exceptionally throaty.

All Africa Twins are outfitted with Honda Selectable Torque Control (traction control) and ABS brakes. HSTC has three levels plus off. An index-finger switch on the left handlebar provides a rider easy, on-the-fly selection between all four settings. The current HSTC setting is presented in bar graph form in the middle of the digital instrument cluster. A light is illuminated on the left side of main display when TC is shut off. The three presets may seem to limit the amount of HSTC adjustability, but do a good job allowing for increased rear-wheel slip without going overboard in the amount of settings available.

Like HSTC, ABS is easily switched off to the rear wheel by pressing a right-side fairing-mounted button. Unlike HSTC, ABS can only be switched on or off when the bike is stopped. Keying the bike off returns both technologies to their default settings: ABS on, HSTC to level three. Using the combined start/stop button to kill the engine while leaving the key on retains your ABS setting but returns TC to its default setting. If you’re thinking that doesn’t quite make sense, I’m in agreement with you.

TC levels are below the clock and next to the gear-position indicator. Speedo, tach and fuel gauge are in the readout above. The entire cluster is a clean, legible design. Note the windscreen is non-adjustable, but the bubble of still air behind the windscreen is remarkable considering the screen’s small size.

Glaringly absent technologies are Ride-by-Wire throttle and the resultant ability to easily enable cruise control. Honda had its reasons for using a cable-actuated throttle, but they sounded shallow, and no excuse will help the Africa Twin when compared in a future shootout to its competitors – which mostly have cruise control. Also MIA (on the manual transmission model) is any type of selectable Ride Modes. With only 94 hp available, there’s no sense shaming Honda for discluding the technology, but it’s become so ubiquitous on new model motorcycles its absence doesn’t go unnoticed.

The big technology here, though, is DCT, and let’s begin by saying that this second-gen version is a big improvement over the original offering. If you’re unfamiliar, DCT is a technology that engages the next gear chosen (higher or lower) while the current gear is still in use – smoothing the gear-shifting process and increasing gear-shifting efficiency.

The left handlebar is a little busy, but the the buttons used most often are the DCT thumb-activated downshifter (below the turn signal switch), the index finger-activated up shifter (peeking out from behind the top right of the grip), and directly above it the HSTC switch. The suspiciously clutch-like lever is actually a parking brake. On the right, next to the hazard lights button, is where you choose Automatic or Manual. Above is the switch for Drive or Sport and also where you select level I, II or III for Sport mode. The N is for selecting neutral.

DCT also replaces the manual toe-shifter with left handlebar-mounted electronic buttons (akin to paddle shifters in performance cars). A rider can choose to manually select a gear with the index finger (upshift) button, or thumb (downshift) button. There’s also an automatic mode with two variations: Drive mode and Sport mode. D mode is for fuel efficiency while S mode is for increased performance; holding onto gears longer and higher into the rev range. At any time a rider can choose to override the automatic settings by selecting a higher or lower gear via the handlebar buttons.

The blue and red coloring indicates the dual clutch and each clutch’s corresponding gears; one for gears 1, 3, 5, and the other for gears 2, 4, 6. DCT models (524.7 lbs) weigh an additional 22 pounds.

New to DCT on the Africa Twin are the three selectable levels within S mode. Whereas level 2 remains the same as the previous DCT, level 1 provides slightly less aggressiveness than level 2, while level 3 provides slightly more aggressiveness than level 2. Unlike Ride Modes on other motorcycles, none of these selections change the way in which power is delivered, they affect the characteristics of the DCT transmission, which is useful depending your riding style, type of road, road condition, and, of course, if you’re on asphalt or dirt.

For off-road riding, DCT models come equipped with a G (gravel) button located next to the ABS button on the right-side fairing. In theory, initiating the G switch reduces slippage within the DCT to better replicate the immediacy of power application to the rear wheel a traditional transmission provides. Riding a DCT model you can feel the difference between having the G switch engaged and disengaged (I preferred the G switch on), but when ridden back-to-back with a standard transmission model, there remains a sight delay, the manual transmission feeling more directly connected to the rear wheel.

I’m an early adopter of new technologies, and previous experience with DCT bikes certainly helped with me being comfortable so quickly on the DCT Africa Twin. By the end of two days of riding, I found myself choosing to be aboard the DCT model, on asphalt or dirt, in Automatic, Sport III mode. If I desired a gear other than what DCT had chosen, it was only a quick push of a button away.

The new DCT also compensates for when you’re traveling uphill or downhill by monitoring throttle opening, speed, engine rpm and gear position. The result is that, when traveling uphill, the DCT will maintain a lower gear to ensure there’s enough drive to overcome the increased drag and, conversely, will downshift sooner when traveling downhill to maintain a consistent amount of engine braking. What DCT does not compensate for is the times when you need quickly pop the front end over a rock or log. Yes, with a hard pull on the bars and full turn of the throttle the front up comes up, but not as easily as finessing a standard issue clutch. Otherwise, slow maneuvering in tight situations is performed well with the DCT, better when the G switch is turned off.

How’s riding with the updated DCT? Up until this event, Honda hadn’t converted me, but after two days aboard the Africa Twin, I can honestly say I’d consider purchasing the DCT model over the traditional transmission. Being that the price increase is only $700, the weight difference is only 22 pounds, and the service intervals/costs are the same, this certainly helps.

The parking brake (beneath the swingarm) on DCT models is separate from the rear brake (top of swingarm) used when riding.

After fiddling around with the different DCT settings on day 1, I found myself mostly riding with the DCT in Automatic, S III mode. Choosing the sportiest S mode is no surprise as, nine times out of ten, it would select a suitable gear for the situation at hand. The times when it didn’t, I simply pushed a button with either my index finger or thumb to override the system and get into the gear I wanted. When riding in the dirt it was especially nice because I didn’t have to remove a boot from a footpeg to select a different gear when standing.

Where I think DCT is incredibly useful is in its diversity of functions. When your significant other is on the back, D mode shifts smoothest in the lower revs and keeps your passenger from helmet kissing you at each stop. Feel really aggressive, put it in manual mode and do all the shifting yourself. Touring? Choose one of the S mode levels and focus more on the road rather than what gear you’re in.

Integrated saddlebag mounts means there’s no additional expense of purchasing saddlebag brackets. The top box does require an additional mount.

DCT worked best for me when I detached my mind from comparing what gear I’d choose or when I’d shift to what the DCT is doing and just let the dual-clutch tranny perform in its own fashion. In any given circumstance, if you’re unhappy with the gear its chosen or how long it’s holding a gear, etc., you can always override the automatic function. The system doesn’t have eyes and cannot intuit what’s going to happen as well as a rider can, so it’s not perfect, and even test product leader, Tetsuya Kudoh, admitted as much, but I was content to let DCT operate, allowing me to pay more attention to the other aspects of riding or just enjoy some sightseeing while I wished for cruise control.

With the popularity of ADV bikes and the likelihood that a lot of owners are like SUV drivers with no serious off-road aspirations, DCT makes off-road riding much more enticing by removing a level of intimidation. Even people with good off-road skills will like the DCT because it reduces some of the concentration spent on shifting and applies it elsewhere. Having ridden both versions of the Africa Twin over the exact same loop, I know for certain I went just as fast and rode just as aggressively on the DCT model as I did on the traditional transmission version.

Outside of DCT, the new Africa Twin will probably find itself with a loyal following among ADV bike enthusiasts. The seating position is comfortable as well as adjustable between 33.46 in. and 34.25 in. with plenty of legroom between the seat and footpeg. The non-adjustable windscreen creates a pocket of still air that seems larger than the windscreen itself.

Suspension is well-balanced with spring rates a little on the soft side. Some time spent adjusting its compression/rebound settings will help adapt it to individual riders and styles, something we’ll focus on when we get one in our possession for a future shootout in 2016. Speaking of which, Honda says Africa Twins should be in dealer showrooms by June. Hopefully your local dealer allows test rides because DCT is something that needs to be experienced. If you do manage a test ride, make sure it’s a lengthy one. Acclimating to DCT and its multiple settings takes longer than a spin around the block.

If DCT isn’t your flavor, you’ll find the standard Africa Twin to be a competent ADV bike with real off-roading capabilities and a (nearly as) capable on-road bike. It’s relatively lightweight compared to some of its competitors (Yamaha Super Ténéré claimed wet weight 575 pounds), and at $13k is priced affordably (2015 KTM 1190 Adventure $16,999). Most importantly, it’s available stateside.

Obligatory splashy water crossing.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire